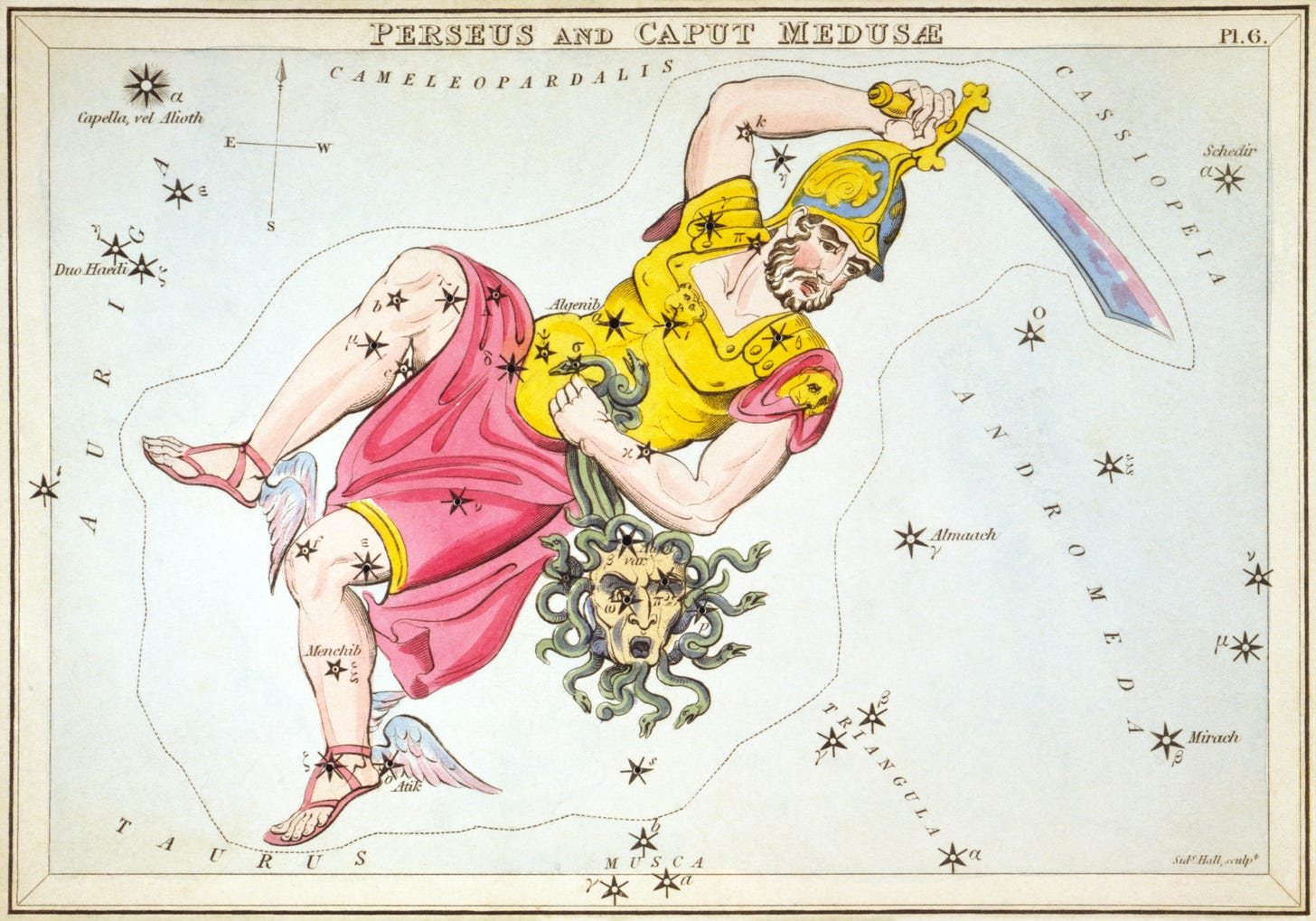

Perseus and Andromeda had nine children – Perses, Alcaeus, Heleus, Mestor, Sthenelus, Electryon, Cynurus, Gorgophone, and Autochthe. Of these children were born many grandchildren, and many great-grandchildren after them, and so on. These descendants include Heracles the renowned hero, Penelope the loyal wife of Odysseus, Helen of Troy, a few Argonauts, and, depending what side of Wikipedia you’re on, an annual meteor shower seen in the northern sky during the early weeks of August.

The Perseids (literally translated as “those born of Perseus”) are so named because they appear most abundantly in the ancient constellation Perseus. This has to do with the angle and direction at which the Earth moves through the string of debris left in the orbit of the comet Swift-Tuttle. Tiny flakes of leftover comet enter our atmosphere and fantastically disintegrate in streaks across the severed head of Medusa looking on from Perseus’ grasp. At the peak of the shower some 100 meteors can be seen in an hour, given perfect conditions. Last year, Taylor and I were in Shenandoah National Park for the peak.

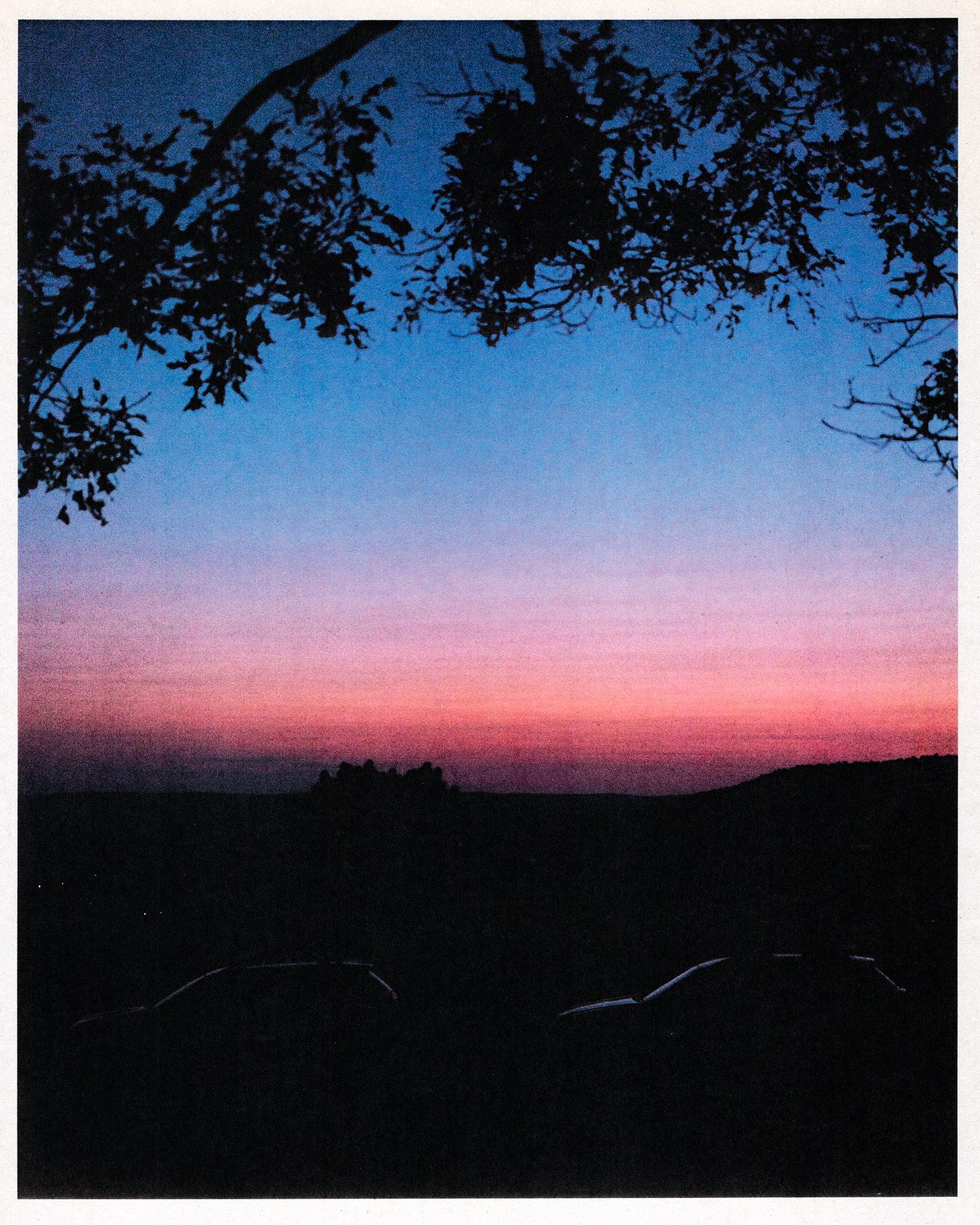

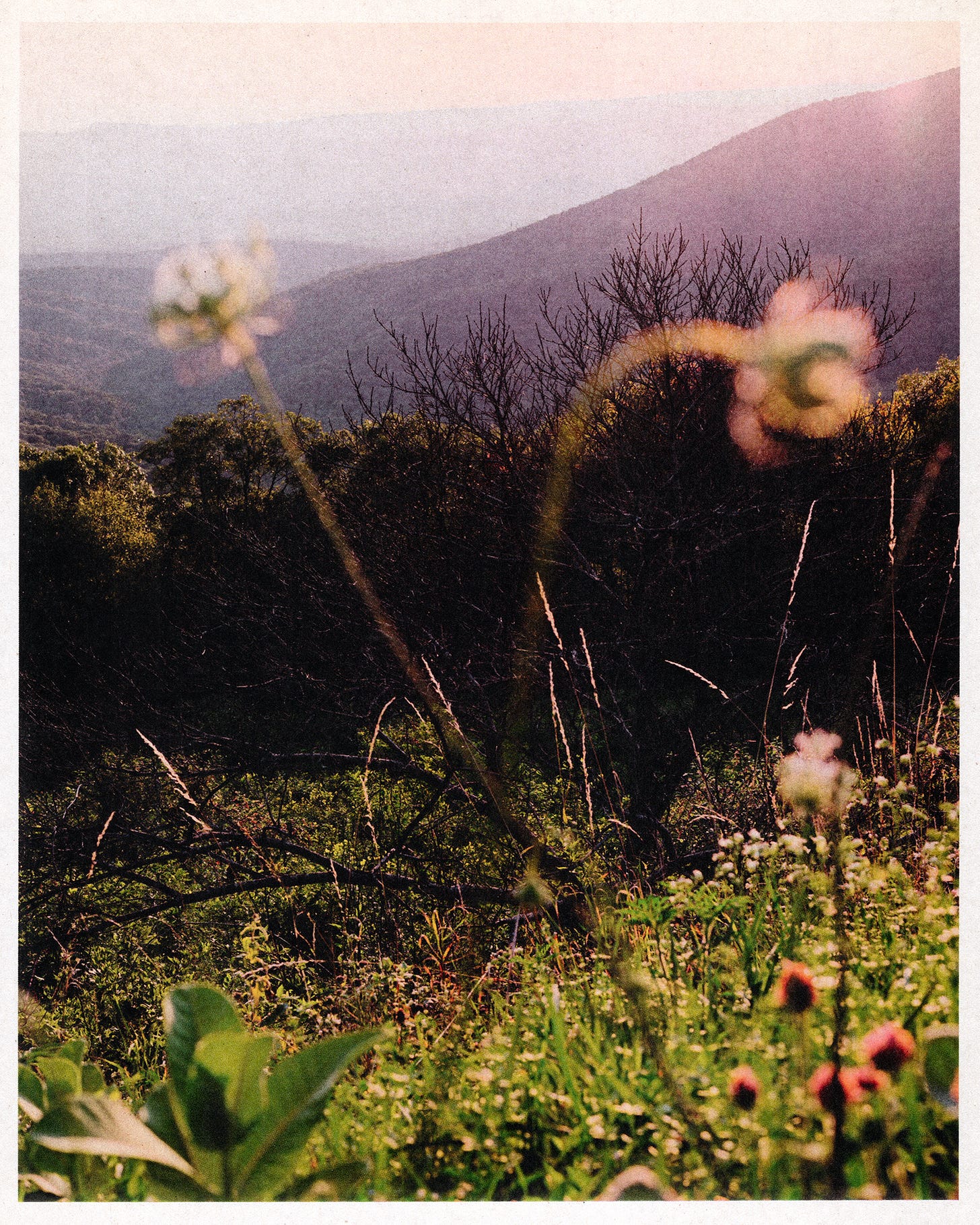

We’ve been to Shenandoah three times total now. For our first visit we camped with two of my high school buddies, and just recently we met up for a weekend with some of my good friends from college. But when we drove down for the 2023 Night Sky Festival it was just us. We knew we might see some meteors, and some other people might be there to see meteors too, but we didn’t quite grasp how big of a happening this really was. The park was packed with campers ready to see the sky light up. The main sky viewing event was held on the night of August 12 at Big Meadow, an appropriately named large patch of soft grass and wildflowers in the heart of Shenandoah. Our Subaru was one in a very long line of cars, and we fought valiantly for a parking spot about a mile from the actual event.

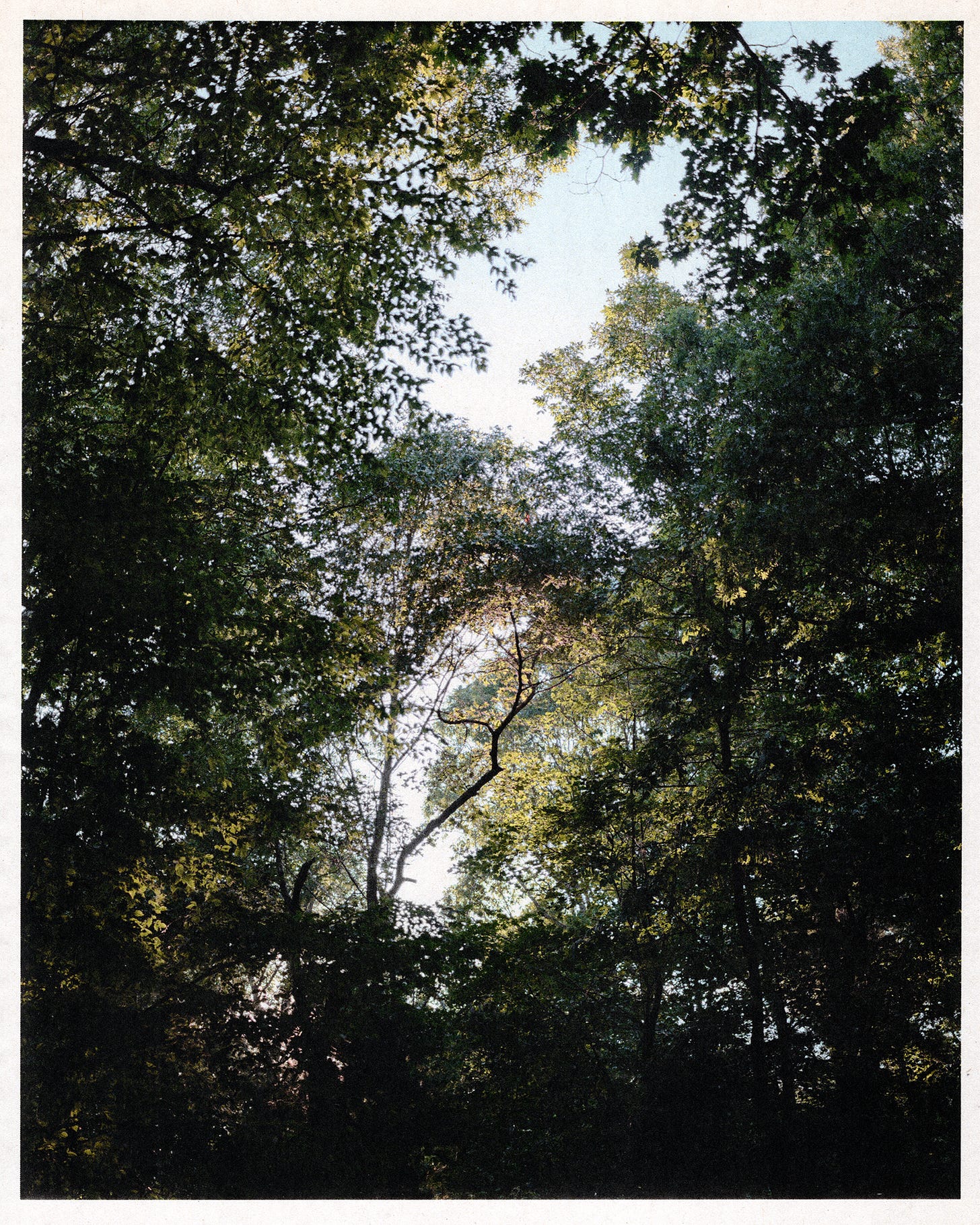

Walking into the dark meadow, we were informed that all white lights (cell phone screens, flashlights, etc.) were kindly prohibited and only night-vision-preserving red lights were allowed past the entrance. Across the field, these red lights illuminated hundreds of people setting up lawn chairs and picnic blankets and picking the comfiest looking spots of ground. We chose our spot and laid down, a great view straight up overhead.

I don’t believe I can do the experience justice describing in words what we saw that night. A meteor shower is easy enough to explain, but seeing so many shooting stars at once, hearing the hushed gasp of a thousand fellow star gazers after each stellar flash, being so far from any major source of light pollution, all made for an experience that I wish I could translate to words. Or images, for that matter.

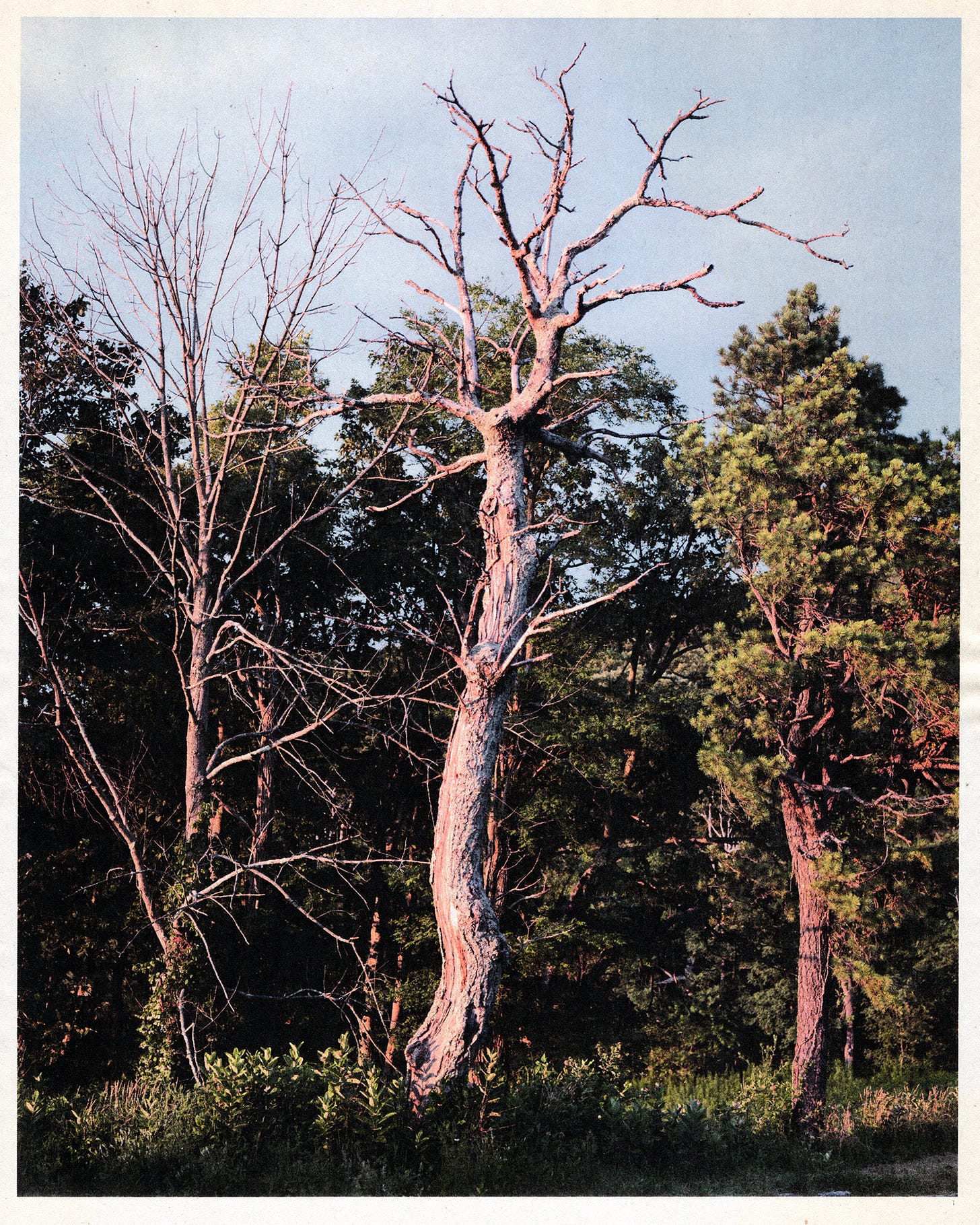

I did have my camera with me, along with a tripod and cable release. I am about as far from an astronomical photographer as stars are from Earth, but I figured if we were there it was worth a shot. I didn’t have a long telephoto lens to focus on a specific small star cluster, or a wide lens to capture as much of the sky as possible. I had the lens I use for everything, from trees and landscapes to mailboxes and cracked sidewalks. I chose a portion of the sky at just about random and pointed my lens there, hoping my shutter would be open at the same instant a meteor happened to flash by.

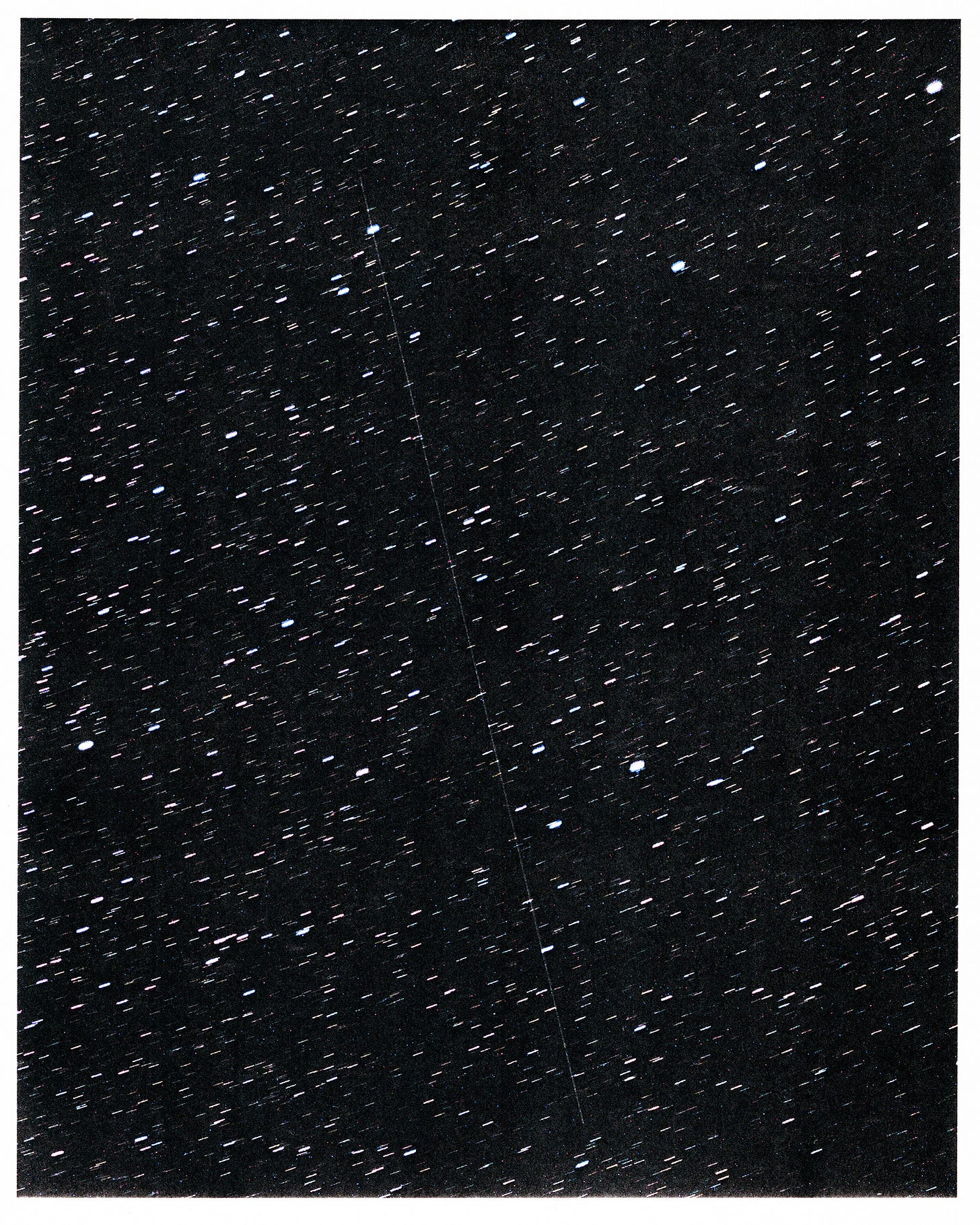

As you might suspect, I didn’t make any prize-winning meteor pictures that night. I took about 30 pictures of the same rectangle of sky, with exposure times ranging from one second to almost four minutes. Most are blurry, and some are so under or overexposed that you can hardly tell they’re of the sky at all. A few are pretty accurate representations of what the sky looked like that night, the Milky Way slightly visible behind a sea of pinprick stars. But at first look, none at all seemed to have captured a meteor.

Back home in front of my computer, I scanned each image at its full resolution for any record of a falling star. I sifted through trails of planes blinking across the horizon, the artifacts of jostled red flashlights as visitors walked in front of my lens, and a whole ton of digital noise. After almost an hour of inspection and my eyes starting to strain, I saw a line through the bottom right corner of image _DSF6787.raf. My experiment had paid off and I celebrated my image of a real-life Perseid by calling Taylor over to my computer to have a look.

However, after Taylor gave me a convincingly proud kiss on the forehead, I kept looking through the images, and so I have to admit I no longer think that thin line cut into the starry sky is actually a Perseid. See, the pictures taken before and after _DSF6787.raf contain a similar subtle white line which over the course of a few minutes (five or so exposures) moved across the entirety of my frame. Where the line stops in one photo it picks up in the next, perfectly connecting when the images are superimposed. I realized, my ego deflating, that I had most likely captured not a glowing, melting meteor but a satellite, flying its steady orbit around the Earth and reflecting a glint of the Sun’s light into my camera. I thought later that even if I lied to myself and claimed that faint line was the trace of a meteor’s path, the image does not come even marginally close to conveying what I felt that night, looking at the stars, laying next to Taylor, surrounded by people that I hope were feeling something similar. The pictures, all in all, were a failure.

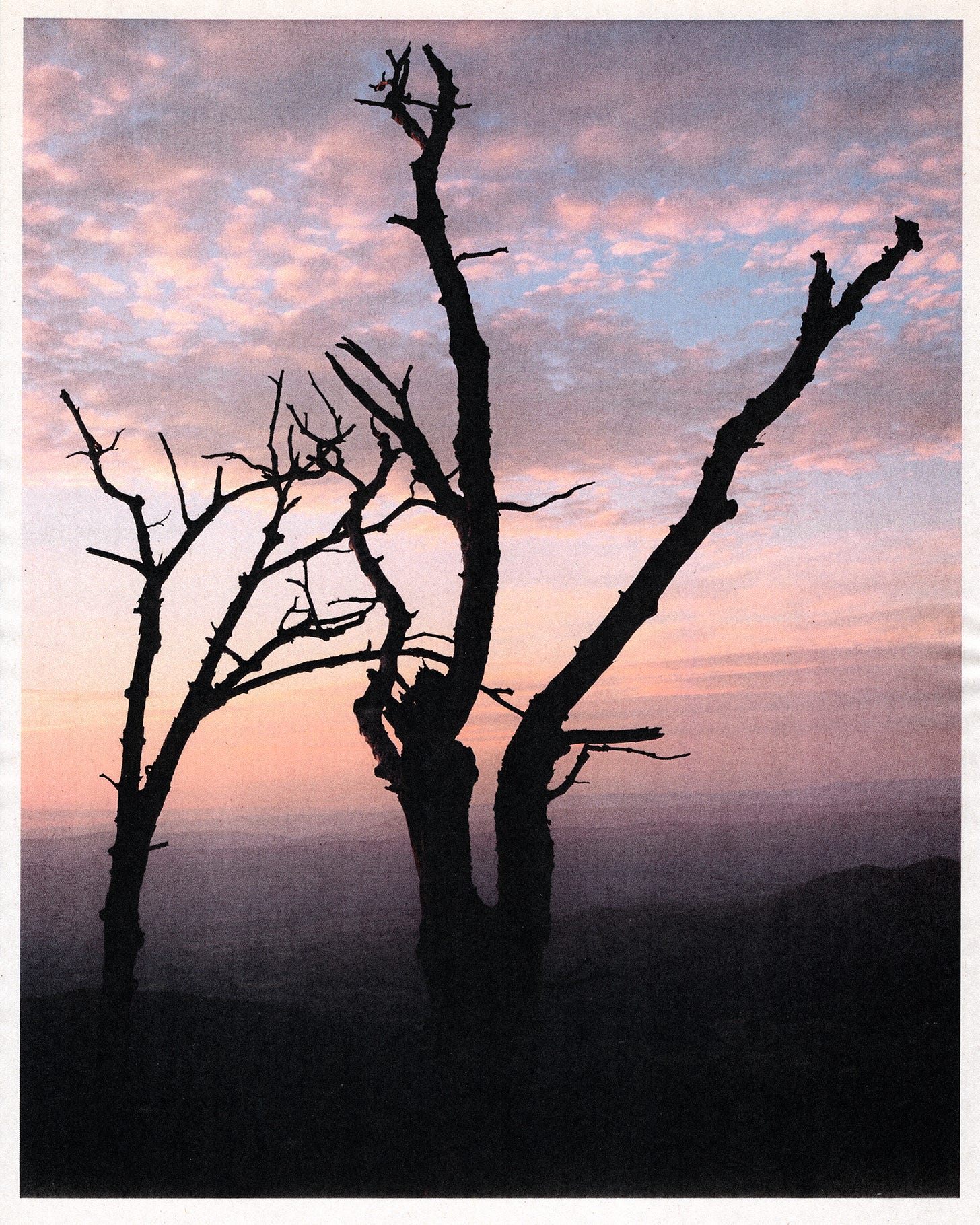

I found myself in Shenandoah again last month, on that trip with close college friends, and as we watched the sun go down on our last full day in the park, we decided to stay out and star-gaze. We weren’t in Big Meadow this time, we were just laying in the grass next to a lookout a few miles south of our campsite at Mathew’s Arm. We saw the first star emerge from the darkening indigo sky, and then the countless others slowly fill in the space around it. We pointed out the constellations we knew (I have the Big Dipper down pat) and made up some new ones of our own. Straining our necks back, we even saw a small shooting star high in the northern sky. “An early Perseid,” Taylor said. My camera, next to me in the grass, wasn’t even turned on.

How much does an astronomer have in common with a photographer? Lenses are instrumental to both, as are cameras and a wide range of fancy imaging equipment. Through those lenses and instruments, both the photographer and astronomer rely on light to do their work. Though, photographers are almost always working with the light emitted from a single close star (our Sun), while astronomers focus on light that has been traveling toward us from countless distant stars and galaxies for millions or billions of years. What the photographer and astronomer seem to have most in common is the act of looking, of observing either our world or the worlds around it, noticing anomalies or particularly fascinating areas of interest, and using the record of their looking to build narratives or draw conclusions about our existence. Or at least that’s the goal.

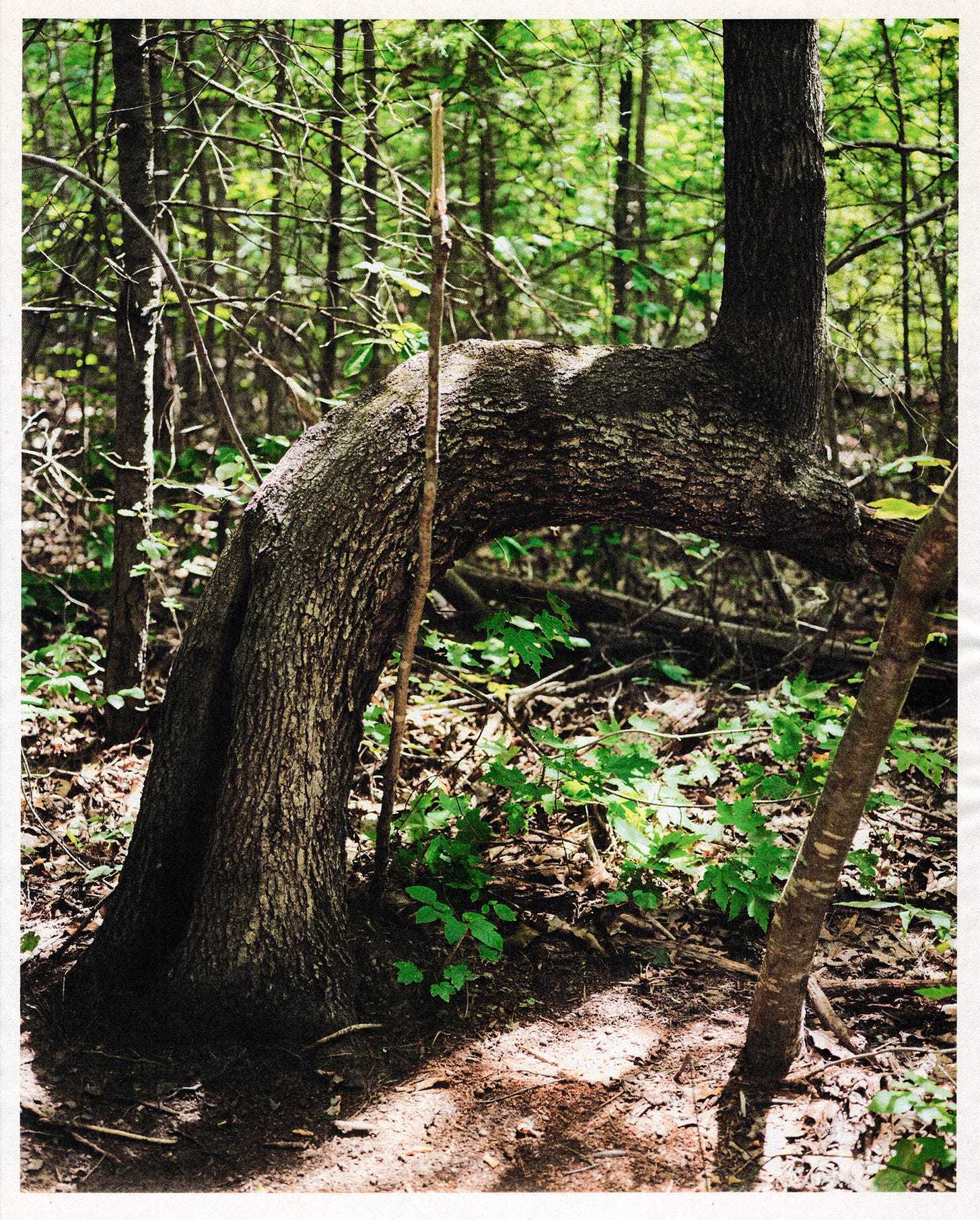

When I have the most confidence in my photographic abilities and my goals as an artist, I feel most like an astronomer. I know exactly where to look and what to look for, as if I’ve done all the complex calculations involved in mapping the path of a comet and can say down to the minute when it will appear in the sky. I have all the constellations of my subject memorized; how everything in front of me connects to everything else, how my pictures form constellations between themselves. I have theories about what is happening out in the world even though I can’t see it – my research points to the existence of something interesting and trusting in that research I go out looking for even those things that I might not ever be able to see. I make representations of these unseeable objects and ideas. I know when to focus on the smallest points, the farthest reaches of my perception, and when to look at large swaths of the world around me all at once. I can compile all of my ideas together and am confident in what I am saying, confident that my conclusions are backed up by the records I have made, and confident these conclusions tell a truthful story that helps others better understand our shared world. I’m not saying I’m always a good astronomer in this analogy (I’m sure at some points I’ve argued the photographic equivalent of “the Sun orbits the Earth”) but I feel in those moments of confidence that, at the very least, I know what I’m doing.

On the other hand, there have been times (especially in the last two years) when I feel like my photographic practice is nothing like that of an astronomer. During those times, I know what I’m looking for just as much as I know which of the stars are actually distant galaxies or when the next comet is due to pass by. Taking pictures is still fun; star gazing is fun even if you don’t know what all the constellations are, but you can’t make a lot of meaning (or a living) just star gazing. And sure, eventually I might take a picture that is pretty good, like seeing a shooting star after a few hours of staring up at the night. But I can’t do that consistently and have something to show for it, just like an astronomer can’t base a theory just on the fact that they saw something weird happen through a telescope.

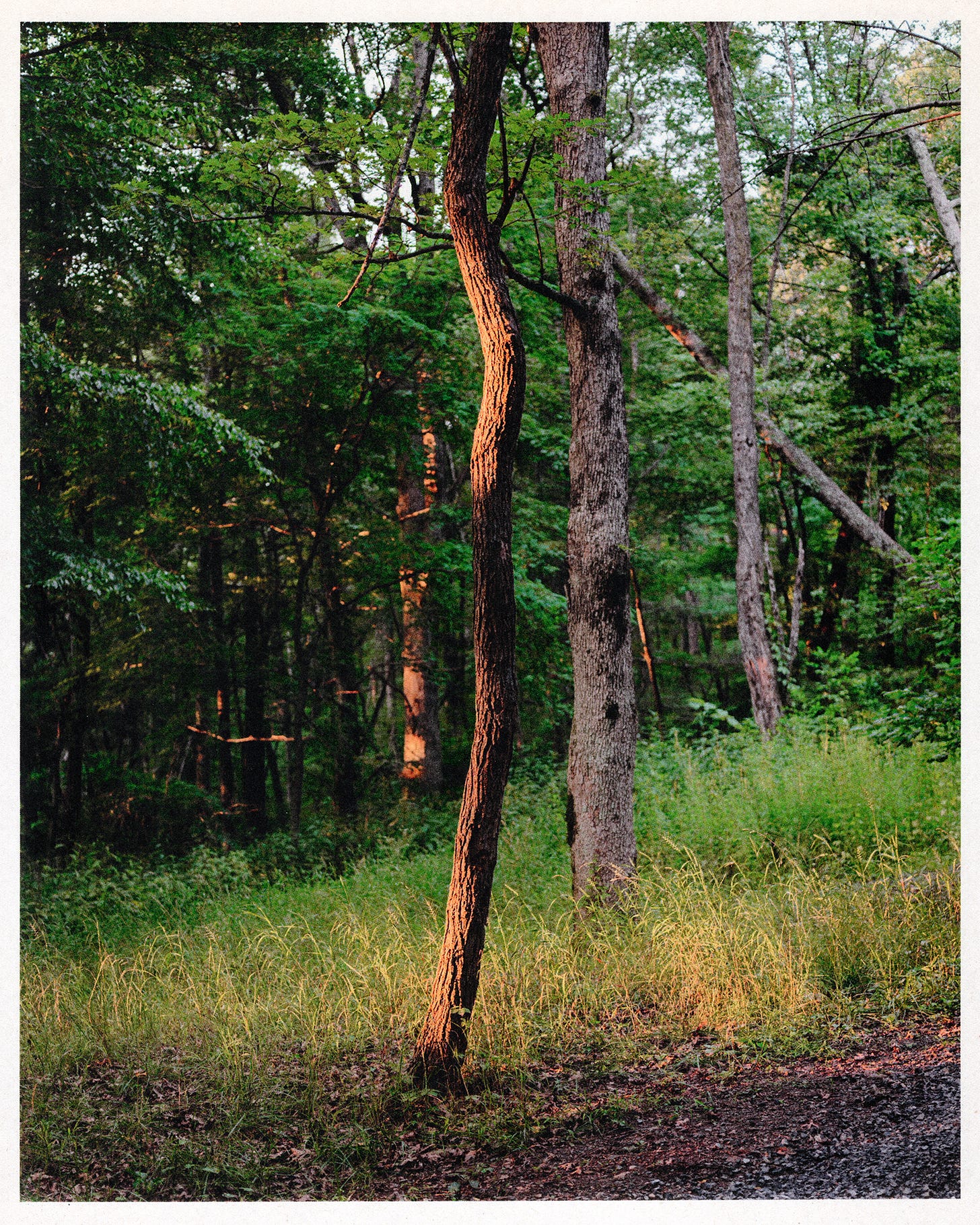

I’ve seen quite a few shooting stars in the last few years, and I’ve taken some pictures that I am relatively proud of (a good few are from Shenandoah). But I haven’t had the direction of an astronomer, to know where to look and to understand the meaning behind what I am looking at. This is, in part, due to my time spent inside finishing up previous work. It might also have something to do with moving to a new place, or working a new type of job, or any other number of reasons known and unknown.

Hopefully, though, I will soon have a new plan. I finally have a new hypothesis, a set of ideas I want to see if I can corroborate with what I find in the world. These ideas involve a particular New Jersey Turnpike rest stop, a few certain streets in South Jersey, a high school or two on Long Island, and probably (terrifyingly) taking a lot of portraits. And as I can finally see my previous project nearing completion, I am excited for this new direction. I am excited to do the hard math, the research and investigation, and the intense exploration that comes with a focused project. I can only guess this is what an astronomer feels like when their months of calculations finally point to the place in the sky where they need to train their telescope. After a few years of star gazing, it is time to start looking.

Are any of these prints currently for sale?

Found immediate fondness for "My one (possible) meteor"

Do we get any inside information as to what that next project will entail? Enjoyed this article!