People don’t seem to keep pictures in their wallets anymore. Gone are the days of the sitcom dad pulling out his wallet and accordioned pictures of his wife and kids springing out, the strip of double-sided laminated prints hanging almost to the floor. I’m not saying that was necessarily a better time (thick wallets are bad for your back) but we all certainly had a different relationship to the printed image in the past. Going back only 25 years, if you wanted to see a picture, it had to be a print of some kind, whether it was in a wallet or on a wall or wrapped around a cereal box. Now, digital displays, our computers and phones, show us the majority of the pictures we see. The printed picture has taken on a new meaning in this time – it has assumed a weight greater than just that of the physical paper it is printed on. Prints, in comparison to digital files, are expensive, hard to make, and a pain to store. Because of this, prints are now saved for special occasions. Prints are for framing graduation photos, remembering a lost loved one, decorating a home, or for the production and sale of fine art. It is this last special category that I want to talk about here.

There are more methods of making a fine art photographic print than there are different models of the iPhone. In addition to modern advances in printmaking, traditional printing practices are still alive and well – prints made with light-sensitive materials in the darkroom are more sought after by collectors than their higher-tech contemporary counterparts. And even inside the alternative print process community there is constant discussion over what process is best. Could it be silver gelatin, or platinum/palladium, or maybe albumin or Van Dyke, or even gum bichromate? I could go on. Each different printing method has its own cost and benefits, and produces its own “look.” A good platinum print is smooth and rich and highly detailed, while gum prints can be wildly colorful and punchy and beautifully soft. These various characteristics are a part of what brings people into the alternative printing space, allowing for the fine-tuning and expression of a very specific style. The character of the print takes center stage, playing as important a role as the composition or the content of the image itself.

But, and I don’t mean to sound blasphemous, some of these prints aren’t good, especially if you use a modern printing technique like inkjet as your baseline. These light-sensitive processes have limitations or inherent flaws in the way they produce an image; a gum print will never be as sharp or as detailed as a fine art inkjet print, and it is hard to find a wet-plate tintype that doesn’t have some sort of scratch or bubble or defect that obscures part of the image. The shortcomings of these prints are often overlooked or justified by their quality in other areas, and in most cases I agree, but the shortcomings are there nonetheless.

An even bigger shortcoming, in my opinion, of these alternative processes is their enormous cost. Chemistry, paper, exposure units, brushes, glassware, enlargers, and the training to use it all is extremely expensive. Some processes are more accessible than others, like cyanotype, which only requires two chemicals, some watercolor paper, and the sun. But other methods, like making platinum prints, require chemistry and paper that can cost up to $15 per print, a hell of a lot when you might have to make a hundred prints to actually be comfortable with the process. These costs can be daunting to the artist and collector when first starting out, and create a sizable barrier of entry into the printmaking world.

But (I can already hear the rebuttal) aren’t modern inkjet printers and prints also expensive? This is true, the initial cost of a computer, printer, inks, and paper to make high-quality inkjet prints is very high. The cost per print diminishes as you make more use of the printer, but the barrier of entry is indeed similar to that of a more traditional light-sensitive process, though you don’t have to make an inkjet print in the dark. However, I’m not trying to argue for inkjet over alternative processes, or to argue that we should stop making light-sensitive prints. I’m here to argue for the adoption of a new kind of print into the pantheon of fine art photographic printing techniques – the laser print.

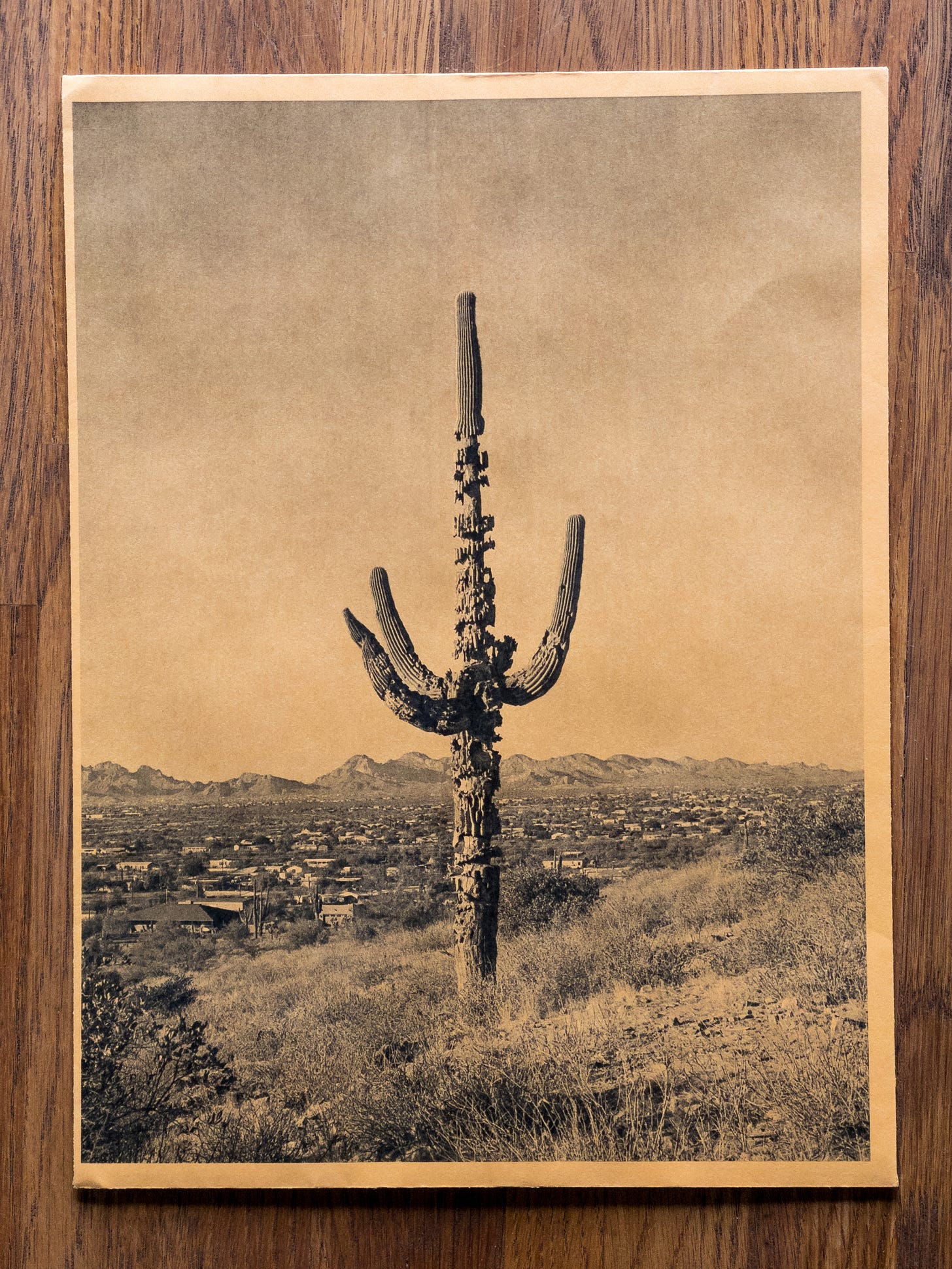

If you have gone to school or worked in an office in the last twenty years, you have worked with a laser printer. Most big copy machines are laser printers, and laser printers are the most accessible home office printers, too. Laser printers are cheaper to run and produce prints in a much higher volume than inkjet printers. Instead of spraying little drops of ink out of tiny jets (like inkjet technology) laser printers screen a thin layer of dry pigment, called toner, onto the paper and then fuse that toner to the paper at high temperatures. This is why freshly-made copies are beautifully warm coming right off the machine. To cut costs, most laser printers only print in black and white and are used for printing documents or making low-resolution copies. But some higher-end laser printers print in color, and do so at a surprisingly high quality. A high enough quality, I propose, to make fine art prints.

So why have laser printers never been used to make prints that hang in galleries? Well, I think there are a few factors at play. First, laser printers were not always capable of printing photographs at anywhere near a high quality. It is only as of recently that full-color, consumer laser printers can accurately translate the image seen on a computer screen onto a piece of paper. This is simply logistics, though. Laser printers now approach inkjet printers in quality and resolution, so why still are they overlooked? I am convinced it has to do with the perception of the medium more than the actual aesthetic it produces. This is not a new phenomenon in the photography world.

Around 1990 Jack Duganne coined the term “giclee” to refer to a modified inkjet plotter he was working with to print large fine art photographic prints. He wanted a word that would let people know these were not typical inkjet prints, which back then were only used as proofs before the final print was made using other techniques. With the new fancy French word, inkjet prints started to become standard in the fine art print industry. The word “giclee” has since come to be used as a euphemism for any inkjet print, especially when someone wants their picture to seem fancier than it truly is. The word is not regulated – I could buy a beat-up ten-dollar inkjet printer on Facebook Marketplace and make a “fine art giclee print” on the back of a piece of junk mail, and I wouldn’t technically be lying. Someone might even buy it. Photographic printmaking has always been just as much about the idea of what the print is as it is about what the print actually looks like.

I think another big part of why laser printing isn’t considered for fine art prints is the subtle elitism that exists in this space. If a technique is cheap, accessible, modern, and relatively easy to learn, can it really be that good? (So question the print snobs). But I say it can be that good. It takes time to dial in a laser printer to get good results, just like any other process. And wouldn’t it make sense that putting the same energy into mastering a process, even if it is cheap and new, will produce a commendable result? To me, it is worth focusing that amount of attention on any process or practice, including laser printing, if an artist finds a way to make it interesting. Hell, there was a time when art snobs dismissed photography as a whole because it was too cheap and easy, compared to painting. If artists didn’t adopt that new way of making pictures, photography might be only considered a utilitarian tool, something for documenting evidence or recording the past. What could we be leaving behind if we don’t explore the artistic possibilities of laser prints?

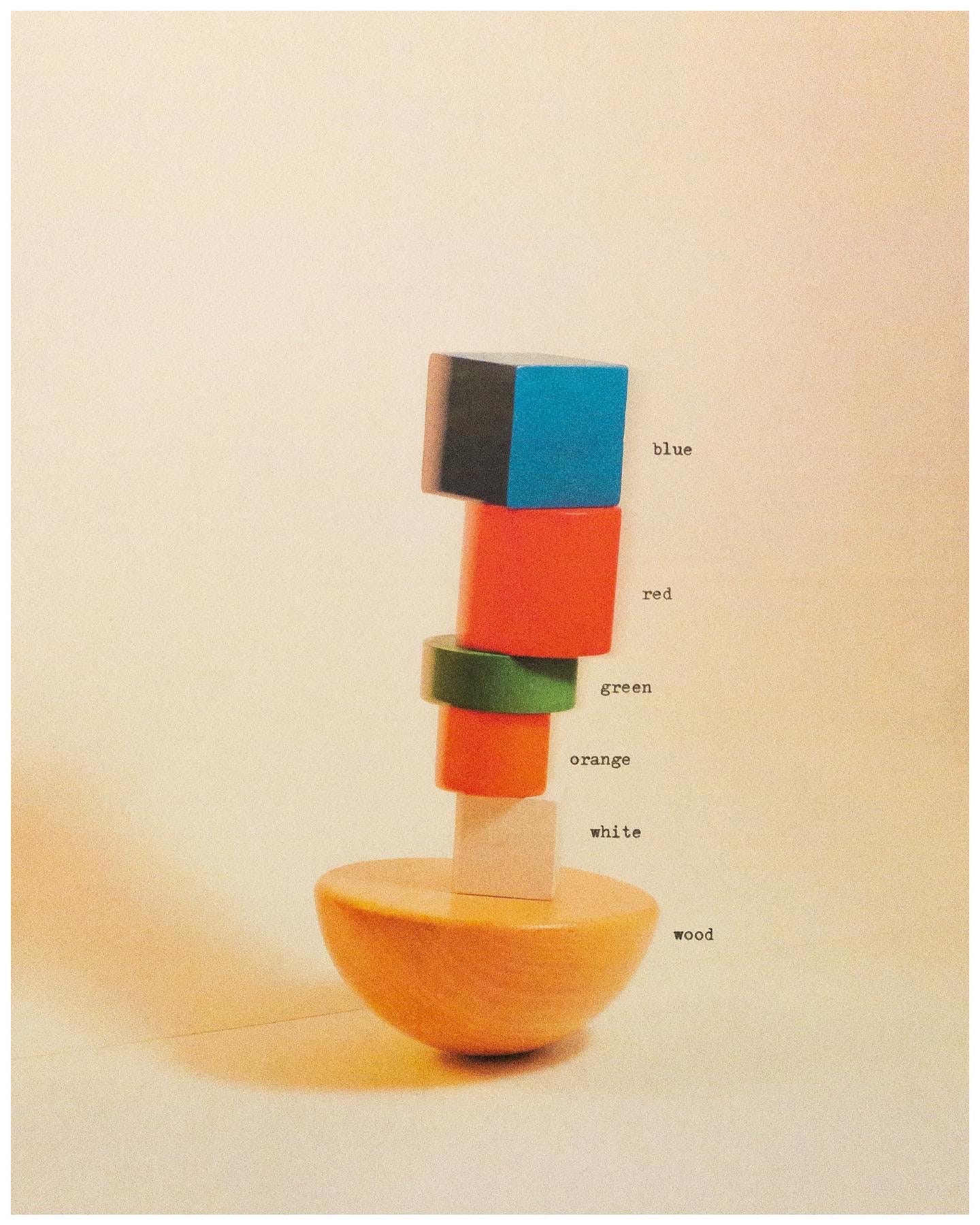

There is nothing quite that different about a laser print and say, a modern silver gelatin print made in the darkroom. They both use highly advanced technology to produce an image on a piece of paper. They both have their own unique characteristics and inherent flaws in how they reproduce the original picture. They both take some time to master, and produce stunning results when done well. The only real difference is how we perceive them; one is considered cheap and commonplace and the other is expensive, fancy, and traditional. Seems a bit unfair.

Am I writing this whole newsletter to justify the mammoth laser printer sitting in my apartment and the laser prints I make with it? Yes, of course. But I am also writing this to encourage other photographers and artists to broaden their idea of what a fine art print can be. In the times we live in, there is something to be said for art that uses fewer resources, that is affordable enough for everyone to own, and that uses modern technology that is readily available. And that doesn’t just go for laser printing, but all the other processes and mediums that might be overlooked or discounted because of our perception of them. This, of course, isn’t to say that we should leave other methods behind – there will always be a place for the processes of the past and the experts that keep them alive, as well as high-end methods like inkjet that push the limits of print quality. We should add to this list as we find new ways to make beautiful pictures, whether through technological advancement or just mastering an obscure technique. Who knows, maybe in sixty years, when laser printers are hard to find and harder to run, collectors will seek out laser prints for their smooth tones or relative rarity, and I’ll make a killing.

If anyone doubts the fact that laser prints can look just as good as inkjet prints, I would love to send you a sample. You can even choose the picture.