Only Posting Prints Online

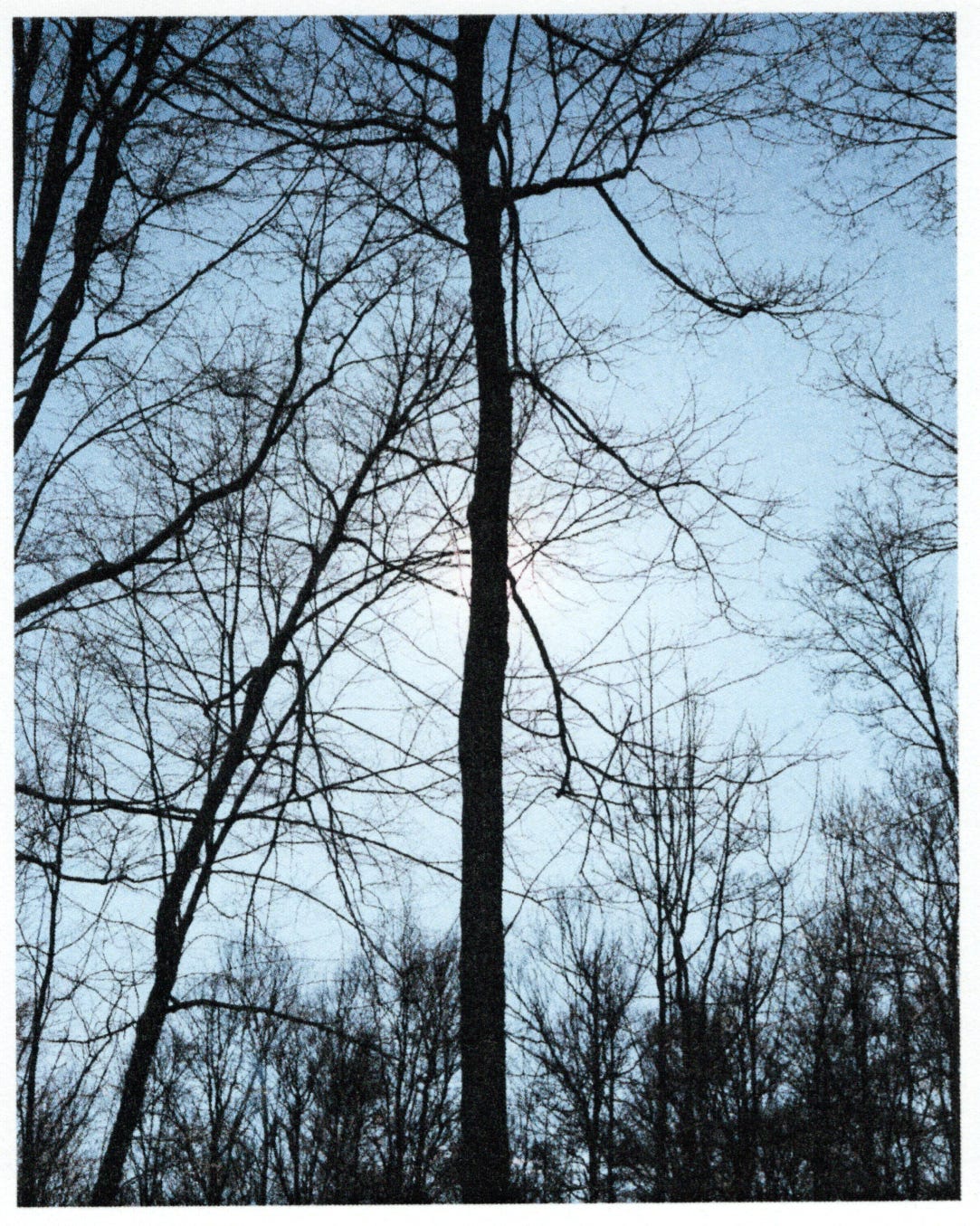

The 2024 Solar Eclipse and Why I'll Never Share Another Digital Image

I was late to share my eclipse pictures. For days after getting back from Erie, I tried and tried to make prints of the photos I took. But I came up short – it seems some of the colors and tones we saw in the sky that day are not reproducible on a questionably maintained laser printer from 2007. I could not make a faithful print of what was in front of me during those few moments, a scene I remember as overwhelming in its unfamiliarity. I had consciously made the best mental image I could of the surroundings, as to accurately recreate it later. And I just couldn’t print a match. On my screen, the digital images came close to capturing that uncanny sky and otherworldly quality of light, as close as I could imagine a digital camera and Photoshop could render that scene. But my printer couldn’t handle it, spitting out muddy skies and washed-out shadows print after print. I have to admit that I gave up, and not wanting to completely miss the online cultural event of sharing all of our (almost) unique perspectives of this grand happening, I posted the digital images straight to Instagram, unprinted.

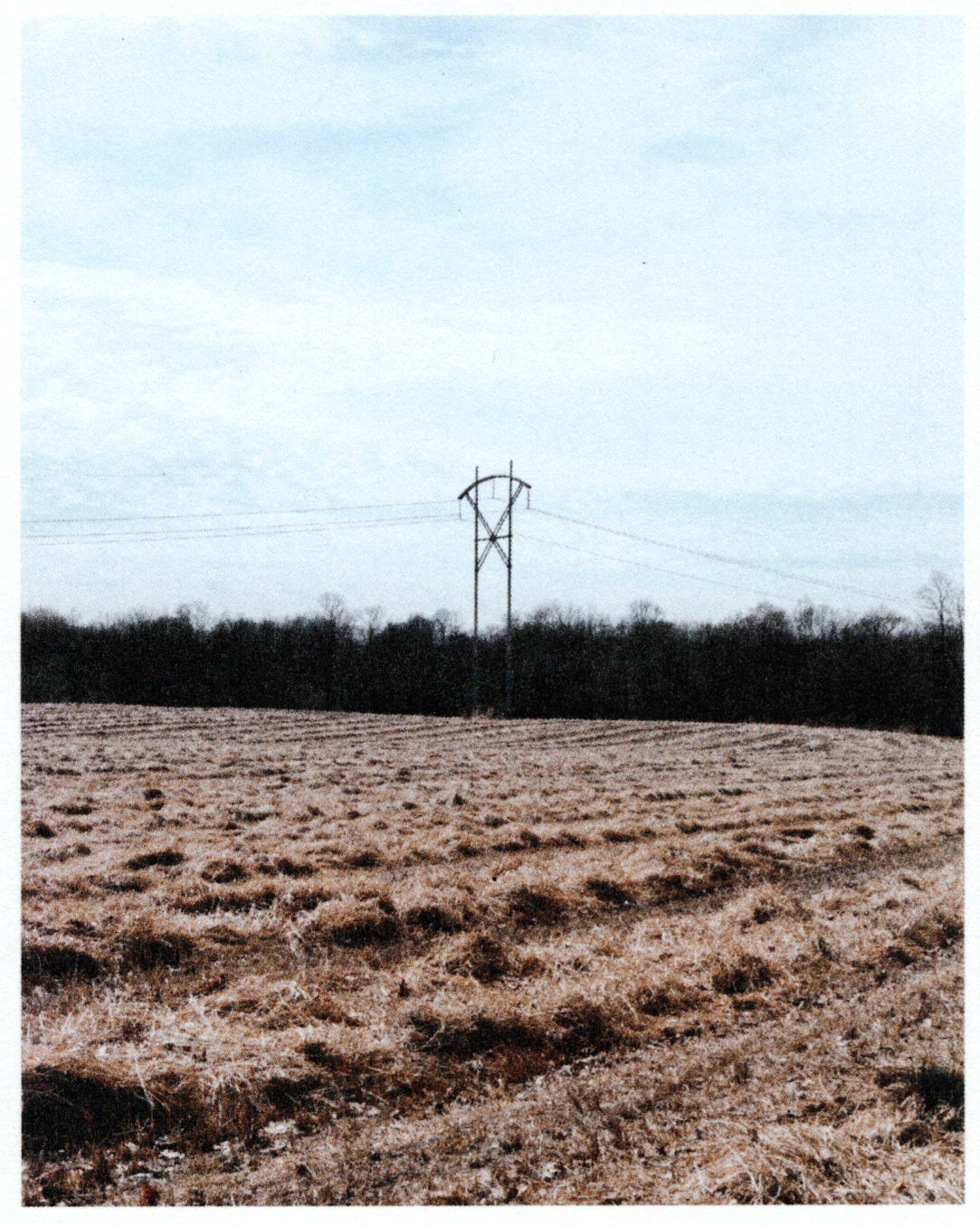

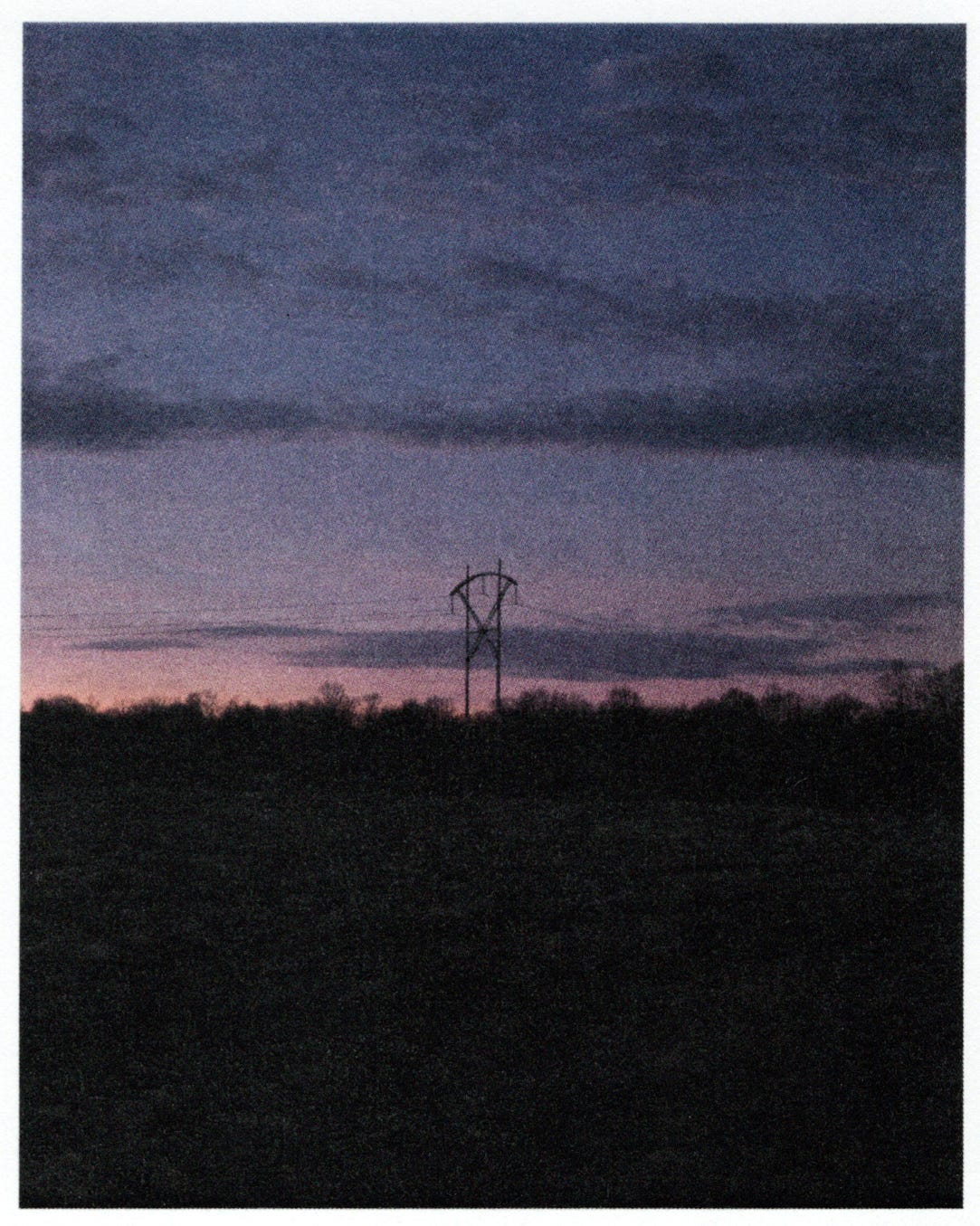

So why did I feel the need to print these pictures in the first place? For well over the last year I have only shared printed work on Instagram (the only place I share my work online outside of my website and this newsletter). Though I haven’t yet standardized this process – I have posted pictures, videos, and scans of both prints and books – each post has been a representation of a physical object. Like currency on a gold standard, every picture I’ve posted since April 2023 has a concrete guarantee of its existence filed somewhere in my studio.

This wasn’t intentional at first. I started sharing prints online to simply share what I was working on and experimenting with. I find printing fun and rewarding and I wanted to show others what I was coming up with. Over time though, the print became more and more essential to anything I wanted to share with the online world. For a number of reasons, I came to see the print as a necessity and consciously limited my new online work to scans and photos of prints. As I examine this practice, it seems that this link between online post and tangible print has gone beyond a purely aesthetic decision and become key to my understanding of how photographs communicate feeling. My experience of this year’s eclipse and sharing the pictures I made around it have compounded these thoughts into a few ideas that I think are worth exploring here.

To take a step back, I admit that the process of posting a digital scan of a physical print made from a digital file does seem convoluted and strange. I use a digital camera and, as many millions of people do, could just share digital files straight from my computer or phone. To break my print-to-post reasoning down, here are four reasons I have for committing to this way of doing things:

The Look

Prints, and scans of prints, look different than digital images. The warmth and grain of the paper, the specific qualities of the ink or toner, the quality of the light reflected off the printed surface; all of this affects how a picture looks when printed. When put together effectively and with intention, these variables produce an image that looks aesthetically more interesting than just the original digital file, even as a tiny Instagram post on a phone.

The Standard

Each printing method, from silver gelatin darkroom printing to office copying, has a set of parameters that need to be observed and respected to make a beautiful print. For example, I know my laser printer can’t hold crisp detail in extremely dark tones so I have to adjust the image around this, making sure nothing is too dark but also making sure the rest of the image feels balanced in contrast. Working within these parameters inevitably leads to prints that look consistent because they were all made with the same set of limitations in mind. Online, this consistency is especially powerful as it links images through a common aesthetic quality and helps a viewer to easily see a set of images as one cohesive whole within the otherwise rigidly structured and segmented Instagram landscape.

The Process

Printing is a very intentional process and involves lots of decisions. More often than not, if these decisions are ignored or made without a specific intention, the print comes out looking bad, worse even than the digital file. The stakes of printing are usually pretty high – you can really mess some stuff up. And there is a steep learning curve to making the tough calls when it comes to what looks best for a certain image, like choosing a printing material or the specific printing method, or just deciding if an image needs to be brighter or a touch more yellow. But learning this decision-making process doesn’t just make someone a better printer, but a better artist overall. The critical eye developed while printing is the same eye used when working on images digitally, or even viewing and thinking critically of others’ work.

The Practice

The most simple of my four reasons: printing is something that I like doing, want to keep doing, and want to be good at. Like a musician playing scales or a baseball player hitting the cages, I need to practice to maintain my knowledge and improve my skills. Printing as much as I can and actively trying to get better will certainly help in the future, both professionally and artistically, when I want to realize bigger, more complex printing projects. Using Instagram posts as my practice is one of the easiest ways to stay committed to making prints.

Those are all pretty practical reasons to print a picture, scan it, and post that scan online and I think I could leave it there, hopefully well explained. But I think there is something else going on as to why I, and many others, are starting to prefer representations of physical media online over strictly digital images. Allow me to briefly list some examples other than myself:

Matt Martin is a fellow laser printer and almost exclusively posts scans of his prints on Instagram, as well as spreads from his laser-printed books and zines. Celeste Fichter shares her physical print interventions through scans, photos, and videos with little to no context, leaving the final interpretation up to the viewer. Ryan Carl posts scans of printed illustrations and designs, and often edits sequences of these prints into quick animations. Diana Bloomfield does an amazing job sharing scans of her alternative process prints, from cyanotypes to three-layer gum prints, all presented online in perfect clarity. Steph Verschuren posts flashy and engaging Instagram Reels of his negative scanning and digital printing workflow, making hyper-short action movies of the whole printmaking process. Willem Verbeeck, one of the most well-known photography YouTubers of the moment, talks often about the process of printing in his color darkroom, and color prints feature prominently in many of his videos. To mention two big photobook names, both Jim Goldberg and Oliver Chanarin came out with books last year that are made up of scans of prints, and the social media marketing for each book foregrounded the physical prints with which the artists worked. And even within popular culture, Billie Eilish (photographed by Keith Oshiro) advertises new Nike sneakers in a print-presenting aesthetic, the crushed black tones and grain reminiscent of pulpy magazine printing of the 70s and 80s.

The list could go on. Online spaces (especially those interested in photography and art) are clearly full of digital images depicting printed media. I would suspect that a lot of these artists have similar reasons as I do for posting work in this way. But I also think that there is an overarching feeling here, a cultural movement in a specific direction, an underlying path that we are all following together despite its inefficiency. And so, this brings me back to the eclipse.

The 2024 eclipse was one of the most viewed eclipses in recent memory, and with the constant advancement and increased accessibility of cameras, it was arguably the most and best-photographed eclipse ever. Almost 50 million people witnessed the event, and I would bet a majority of them took at least one (probably decent) picture. More people probably witnessed the 2009 eclipse, but a camera-equipped cell phone was still somewhat of a luxury, entry-level camera equipment was more expensive, and the cameras people did own were much less capable than they are today. I know this is impossible to prove outright, but it is not outrageous say that more photographs exist of the 2024 eclipse than any other.

And on top of this, the pictures of this eclipse are ultra-accessible, posted to view for free on Instagram and TikTok and just about anywhere else pictures can go online. In 2024, someone who did not see the eclipse in person might have the best opportunity ever known to see what it was like after the fact. We are now able to look through the countless lenses that were simultaneously pointed skywards just by tapping on our phones.

And yet, millions of Americans traveled great distances to see eclipse with their own eyes. This was almost universally understood – no one we know questioned our decision to drive eight hours to Erie to witness totality. We all want to see this kind of thing for ourselves, to be in that moment. We want to see the real thing, and that usually means going out of our way to do so. We know the difference between looking at the real moon block out the real sun and seeing the same event displayed on a screen, no matter how high the resolution. We want to see something that exists.

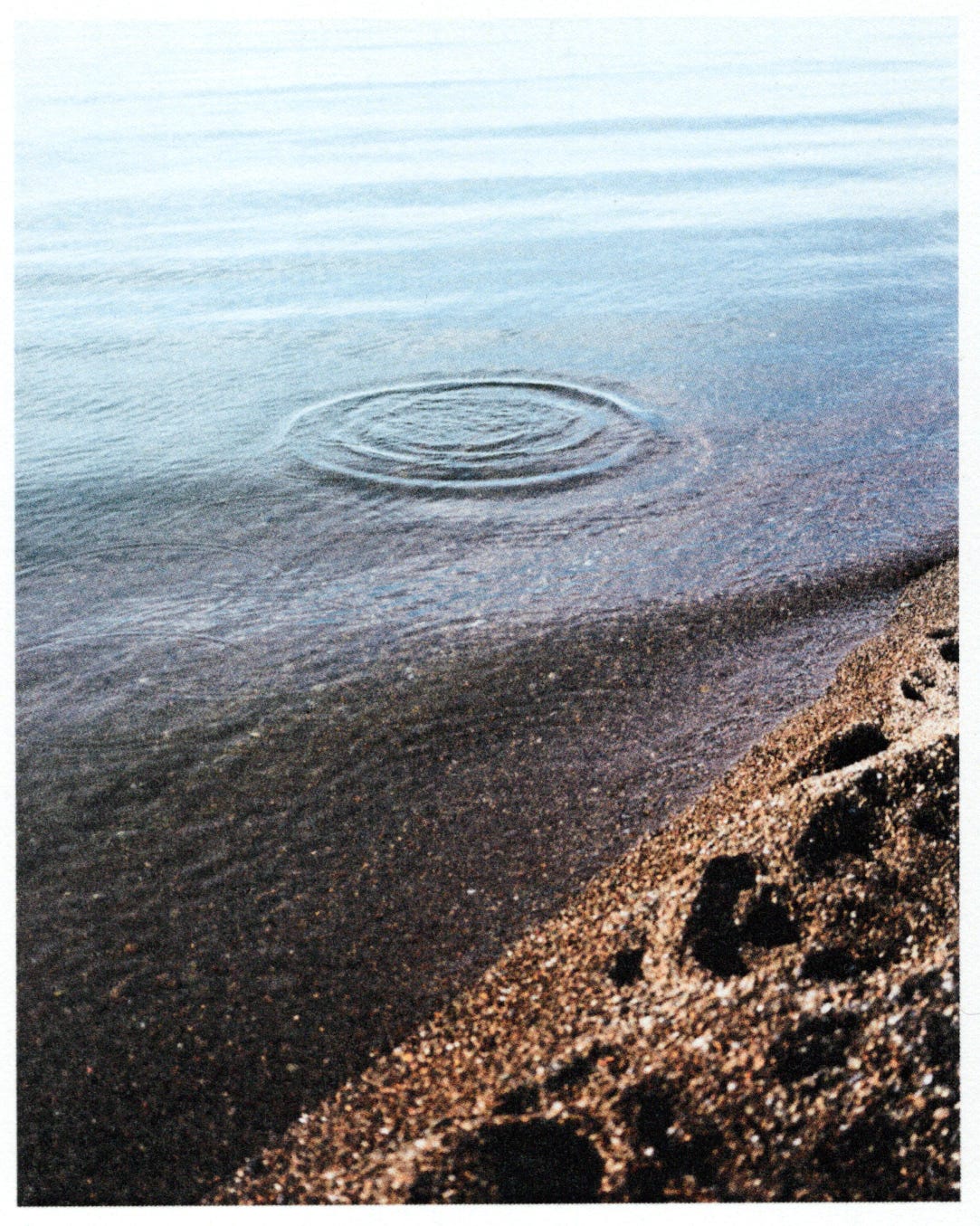

When I look at art online, now more than ever, I have the same feeling – I want to see something that exists. I know a print isn’t going to magically pop out of my screen, but I’m always hoping to see something that I could, if I tried hard enough, eventually see with my eyes or even hold and touch with my hands. Knowing that what I am looking at exists somewhere out there in physical space changes how I think about that piece of art. That knowledge of a work’s concrete existence lends power to whatever message the artist is communicating. Even if I don’t know exactly how it was brought into the world, I know how many factors had to line up for the artist to create something real and then share it with me. Through creating art of quality that is also tangible, even if the actual real-life object can’t be shared with the world, the artist communicates a level of passion and dedication that encourages the viewer to look at the subject depicted with the same intensity.

I love looking at art in person, in a gallery or museum or in public, and thinking about the intersecting trajectories at work — an artist finding the resources and ideas to create art in the first place, that artist finding a venue willing to publicly share what they made, finally finding myself physically in that place and the art being in that place as well. My physical being and the work of art align only briefly, but for that moment the rest of the world is blocked out, pure appreciation and wonder and inspiration and awe encircling the work in my mind just as the sun’s corona undecsribingly wraps around the moon.

Unfortunately, looking at physical objects is not how I or the majority of people now most often look at art. But we can try to recreate that experience with what resources we do have, taking advantage of the internet while simultaneously preserving that magic of seeing something real – that exists.

great morning read ☀️ really love the tree w holes in it (on index card)