I don’t know if I would consider myself a particularly squeamish person, but there are a few things that just really get me. Some stuff that puts me on edge is pretty self-explanatory – I’m not a big fan of seeing my own blood, or the literal sound of nails on a chalkboard. Other revulsions I can’t explain at all, like the awful feeling I get when I see a plant growing inside of its own fruit (view example at your own risk).

The specific aspect of my squeamishness that I want to talk about here though, something that I have been trying to figure out for some time, is my deep, inexplicable aversion to defacing or harming a book. I have never in my reading life been able to dog-ear a book’s page, no matter if it was a Magic Treehouse chapter book or a fifty-cent used paperback. I find it hard to make notes in a book’s margin, and highlighting anything has always seemed sacrilegious. I avoid breaking the spine of hardcover books at all costs, and store dust jackets safely in a drawer so they don’t get tattered while reading. I know it's normal for a person to take good care of the books they own, but it seems a little extreme that I can't even bring myself to mark one up. It just doesn’t make much sense. I mean, I’ll watch James Bond blow bloody holes in henchman any night of the week, but if there was a scene where 007 has to brutally rip the pages out of a book, I think I would have to look away.

These feelings about harming printed matter might go all the way back to getting my first library card in elementary school. Our school’s librarian made it clear that there was a right way and a very wrong way to treat a library book, and if she caught anyone folding corners or drawing doodles their library privileges would be swiftly revoked. I suspect I have never since made the distinction between a library book and a book that I own. It is easy to understand why we shouldn’t mark or deface a library book, a collective practice in preserving books for the free use of everyone else. But why can’t I mess up my own books? I suspect part of this also comes from the value, both sentimental and monetary, I see in my books. I spend an embarrassing amount of the money I set aside for “fun” on books, and so I can’t help but feel that defacing these semi-expensive objects is hurting my investment (if only one could retire on savings made up of bird books and multiple paperback copies of DUNE). And these financial considerations are easily overshadowed by my emotional connection to my books – the thought of defacing a book that was a gift or that I connect to an important time in my life seems plain evil. But I know the fear of harming a book, as deep-seated as mine is, isn’t normal (it doesn’t even have its own -phobia).

So, I recently put myself through a type of book-destruction exposure therapy.

I was in the book section of Goodwill when a heavily annotated and highlighted book on complex math got me thinking about all the weirdness I feel towards marking my own books. The rainbow of arrows and scrawled notes in the margins of this tattered textbook made it suddenly obvious that some people felt differently. In an attempt to broaden my understanding of how others interact with books, I decided then that I would buy a book that day with the sole purpose of physically altering it. I poured over the stacks and decided on an old thesaurus, drawn to its rugged exterior and the thought that it would probably get thrown out eventually anyway. The world has almost completely moved on from physical reference books, and so feeling the least bad about possibly destroying this book compared to another, I bought it. It cost $3.29.

At home, I set the tome down at my desk and opened it to a random page. I dog-eared the top right corner, making a sharp crease by running my thumbnail swiftly over the fold. The soft sound of the old, thin paper crackling as I did so was satisfying. I made a few doodles with a pen on the same page and was surprised to see how little the pen bled through on the opposite side and the page beneath. I closed the book, and it was still the same thesaurus that I bought a few hours before, my slight alterations unnoticeable from the outside. If I put the book on my shelf I might forget I had done anything to it at all. Some of my initial hesitancy started to melt away.

I opened the book again to the same now dog-eared page, and tore it out suddenly. The paper split about halfway down the page and the tear curved in a graceful arc toward the bottom corner, leaving the lower part of the page still bound to the book. I felt for a moment awful seeing both incomplete halves of the page, lines cut off mid-word, some letters lost completely in the uneven tear. But I also felt the need to get it right. I was now committed to tearing a clean page out of the thesaurus, to see what a perfectly whole, intact leaf would look like. After a few (or perhaps many) more failed attempts and some close inspection of the book’s binding, I came to the sad conclusion that I would have to completely unbind the book to get at a whole page. In for a page, in for the book; I’d see this experiment to its logical end.

Assembling the tools necessary to take this book apart (a sharp knife, pliers, weights for loose pages) I started to feel like da Vinci preparing to dissect a corpse for the sake of Knowledge or Art. Only I’m no genius and certainly not as methodical as Leonardo – this book autopsy at points felt more like book butchery. The book took longer to disassemble than I would have expected. I had to cut the faux-leather covers off to get at the thick spine, which was held together with more glue than a first-grade noodle-art project. I ripped off the thin board spine-backing with the pliers, jagged chunks of yellow-aged adhesive and dangling thread coming with it. Now I could clearly make out the individual signatures of the book, or the folded packets of pages that are sewn together. One by one, with my bare hands now, I ripped the sixty-or-so-page leaflets from the bigger bookblock, until each lay on its own. With the signatures freed from both the spine and their neighbors, I could now tear a clean page from anywhere in the book, as easy as snagging a sheet from a roll of perforated paper towels. Each perfect rectangle of torn-out page was beautiful, worth my effort to obtain. My book butchery was complete, the flanks and steaks of loose pages and stacks of signatures strewn about my desk. The deed was as done as it could be.

What did I learn from this experiment? Foremost, I learned that mass-market books (especially reference books it seems) are built to last. It was not a breeze to break this book down to its simpler parts, and to me this shows just how much energy and expertise goes into making a book durable. We take for granted what goes into making a book last longer than a modern household commodity– I’ve never used a cell phone that is more than a decade old at most but I own and have read books printed in the 1920s.

A book is a rugged, dependable way of transferring information. I spent the better part of an afternoon trying to pry one apart (though carefully) and could still use it as a thesaurus, mostly. When I think of digital information, in comparison to books, it seems glass fragile – hard drives are known to fail, unbacked-up phones break, your whole website goes down because one comma of style code is in the wrong spot. It doesn’t take much for a piece of digital media to just disappear. After seeing what it would take to physically render a book useless, I have a newfound appreciation for how tough a book really is.

I want to say that this is in no way an encouragement for the wanton destruction of books. I will still treat the books that I own with great care. But I won’t be scared if some get a little bumped or torn, or if I really do ever find the overwhelming need to make a small note. The books can take it.

Closing Thoughts (Read: The Self-Promotional Part)

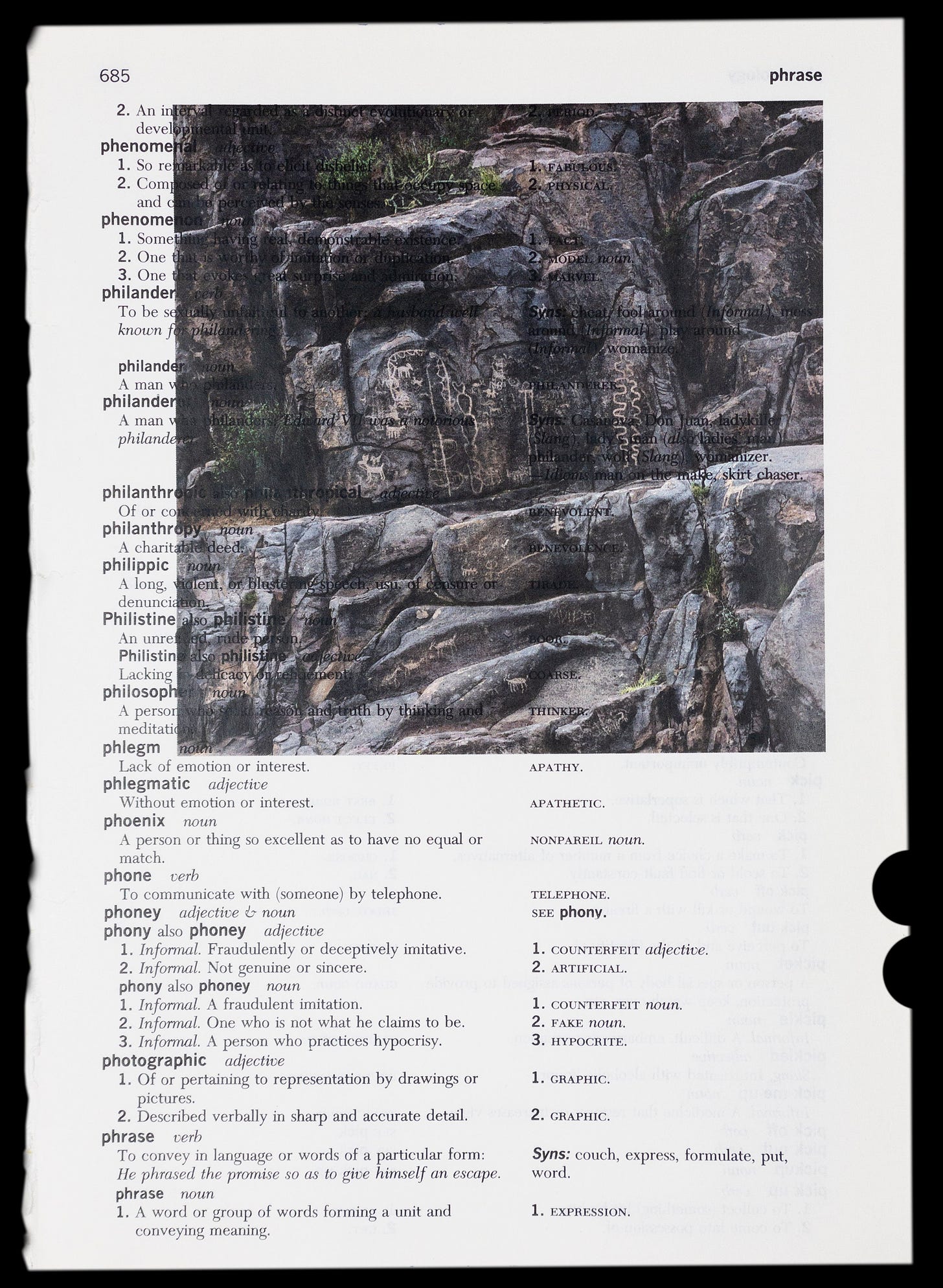

With all these loose thesaurus pages lying about, I decided pretty quickly that I would need to make something out of them. I couldn’t let them just go to waste. So I spent the next afternoon making a set of laser prints on pages I found interesting. The final piece doesn’t have much to do with tearing a book apart, but I think of it as a slight tribute to the sacrificed thesaurus nonetheless. I was fortunate enough to hang this set of thesaurus prints in the most recent members’ exhibition at Art Intersection, which is now up until April 30. If you live outside of Arizona and want to see a high-res reproduction of the work on the wall, click here.

I personally think you inherited your feelings about altering a book from your mother. 😊

These pages are beautiful. Awesome work.